Appropriations, Obligations, and Outlays: The Three Stages of Federal Spending

If you've ever ordered food at a nice restaurant, you already understand appropriations, obligations, and outlays.

Every federal budget document uses the same three terms. Every spending headline throws them around. And almost everyone—including people who should know better—gets them confused.

Fortunately, the concepts are pretty simple. It's like going to a nice restaurant.

When you sit down, you have money available to spend—maybe $250 in your wallet or bank account. That's your appropriation: spending authority that exists but hasn't been used yet.

When you order the entree, you've made a commitment. You owe the restaurant money now, even though you haven't paid yet. That's an obligation: a binding promise to pay.

When the check comes and you hand over your debit card, money actually changes hands. That's an outlay: cash leaving your account.

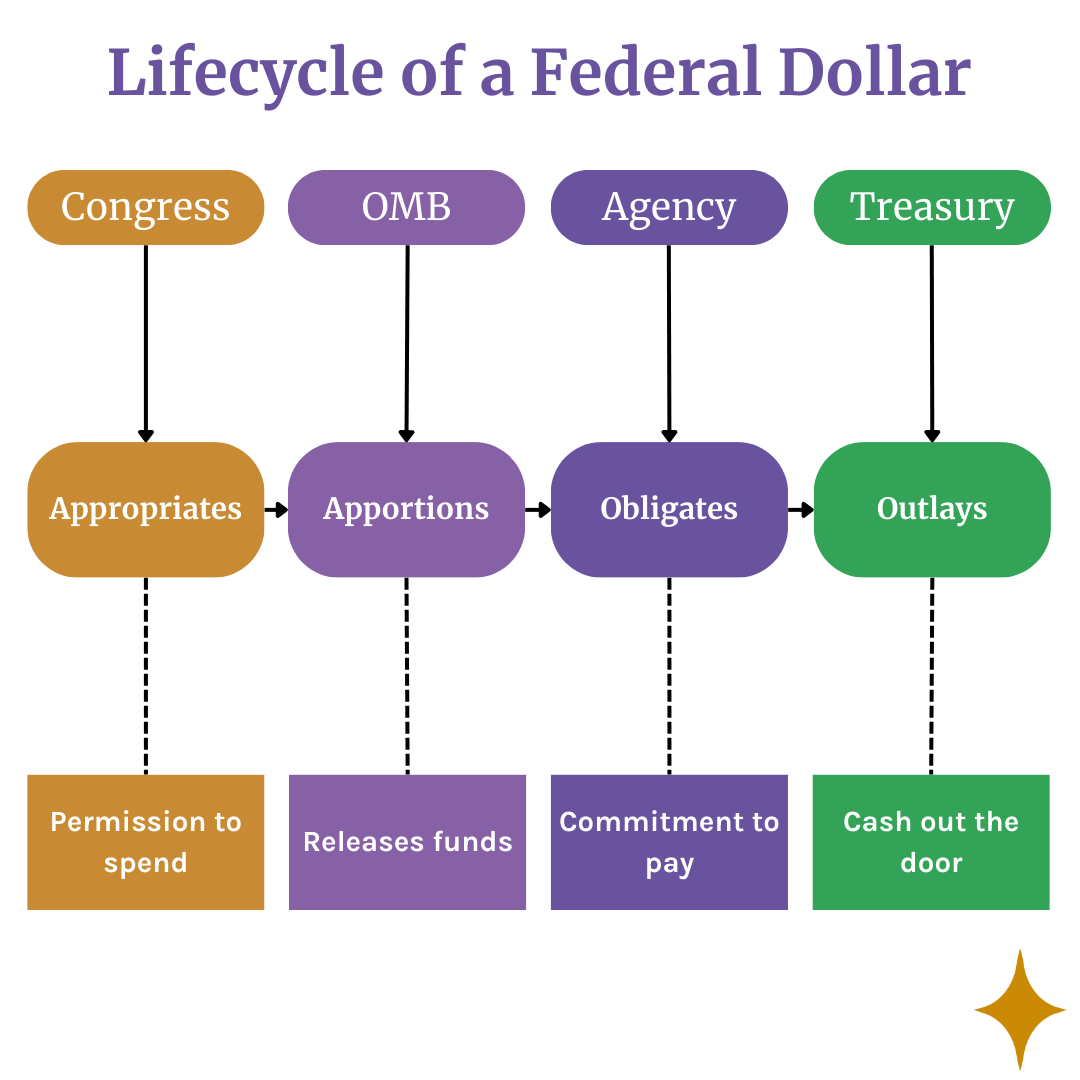

Federal spending works the same way. Congress provides the authority (appropriation). Agencies commit the money (obligation). Treasury pays the bills (outlay). These three stages appear in almost every budget document—and confusing them will lead you astray every time you look at federal spending data.

The 60-Second Version

| Term | What It Means | Restaurant Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Appropriation | Congress provides budget authority | $250 in your wallet when you sit down |

| Obligation | Agency makes a binding commitment | Ordering the entree |

| Outlay | Treasury makes actual payment | Paying the bill |

| Unobligated balance | Appropriated but not yet committed | Money still in wallet after ordering appetizer |

| Obligated, unexpended | Committed but not yet paid | Food ordered, check not yet paid |

| Expended | Paid out | Bill paid, you leave the restaurant |

When someone says the government "spent" $100 million, which stage do they mean? Appropriated? Obligated? Outlaid? The numbers at each stage can be very different, and the answer changes what you're actually measuring.

Download a quick visual guide to approprations, obligations, and outlays.

Appropriations: The Starting Point

An appropriation is a law that allows federal agencies to spend money from the Treasury.

When Congress passes an appropriations bill (and the President signs it), it creates budget authority—legal permission for an agency to incur obligations up to a specified amount.

Key points:

- Appropriations come from Congress (Article I, Section 9: "No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law")

- They specify the purpose (what the money is for), the time period (when it can be used), and the amount.

Types of Appropriations

Think of the fiscal year like a restaurant shift. When the shift ends at midnight, certain things have to be settled.

By duration:

- Annual (one-year): Must be obligated by September 30—when the shift ends, unspent money disappears. Use it or lose it.

- Multi-year: Available for obligation over 2-5 years—like a gift card that expires after a set period, or the second bill you get from your new server after you stay a long time.

- No-year: Available until expended—money that stays in your wallet until you spend it, no expiration date.

By specificity:

- Definite: A specific dollar amount ($500 million)

- Indefinite: "Such sums as may be necessary" (rare for discretionary spending)

Appropriation ≠ Spending

This is the critical insight: An appropriation is permission to spend, not actual spending.

Congress can appropriate $1 billion for a program. If the agency never signs a contract or awards a grant, no obligation occurs. If no obligation occurs, no outlay occurs. The money sits there—appropriated but unused.

This is why tracking just appropriations doesn't tell you what's actually happening. You need to follow the money through all three stages.

- What is an Appropriation? Understanding Congress's Power of the Purse

- How Appropriations Work: Duration and Distribution

Obligations: The Commitment

An obligation is a binding agreement that will require the government to make a payment.

Not just anything counts as an obligation. Federal law is specific about this.

The Recording Statute (31 U.S.C. § 1501) defines exactly what can be recorded as an obligation. An agency can only record an obligation when there's documentary evidence of:

- A binding written agreement - Contracts, purchase orders, formal commitments

- A valid loan agreement - Government commits to disburse funds

- An order for goods or services - Placed in good faith and reasonably expected to be filled

- A grant or subsidy - Payable from the appropriation

- A pending litigation judgment - Likely to result in payment

- Employment services rendered - Salaries, benefits as earned

- Other legal liabilities - As specified in law

You can't just decide to spend money and call it obligated. There must be a documented, legally binding commitment that creates a liability for the government. It's the same in a restaurant - if you don't tell the server that you want food, you're not going to get food and you're not going to get billed for it.

Why the Recording Statute Matters

The Recording Statute exists to prevent agencies from "parking" funds by creating fake obligations to avoid returning money, recording obligations prematurely before a real commitment exists, or manipulating reported spending through loose obligation definitions.

If an obligation doesn't meet one of the statute's categories, it's not a valid obligation—period. Auditors check this.

Common Obligation Types

In practice, most obligations fall into a few categories:

- Contracts: Agency signs a contract with a vendor

- Grants: Agency awards a grant to a recipient

- Personnel: Employees earn salaries (obligated as earned)

- Purchase orders: Agency orders goods or services

- Loans: Government commits to disburse loan funds

The moment the agreement is signed or the order is placed, an obligation is recorded—even though no money has changed hands yet.

Timing

Obligations must occur before the end of time period specified in the appropriations statute. This is called the period of availability. More many appropriations, this is a single fiscal year, but Congress often grants multiple fiscal years to make obligations or, in some cases, allows funds to be used until expended (no-year).

Obligations Can Change

Back to the restaurant: You ordered the steak, but the meal isn't over. You might order dessert and a cup of coffee, another drink, or an appetizer you forgot. Your obligation grows. Or maybe you change your mind and cancel the dessert order—your obligation shrinks.

Federal obligations work the same way:

Upward adjustments (obligation increases):

- Contract modification adds scope

- Grant recipient requests additional funds

- Cost overruns on a project

Downward adjustments / Deobligations (obligation decreases):

- Contract comes in under budget

- Grant recipient doesn't use all awarded funds

- Project canceled before completion

These adjustments happen between obligation and outlay. The final outlay may be higher or lower than the original obligation—just like your restaurant bill might differ from what you expected when you first ordered.

When funds are deobligated, they become available again (unobligated balance)—like getting money back in your wallet because you canceled the dessert.

The Legal Weight

Obligations aren't suggestions. They're legally binding commitments. If you "dine and dash" at the restaurant, the restaurant might call the police or you might end up with a payment demand. The same concept applies in budget execution-if the government doesn't honor an obligation they might end up in court.

Once an agency obligates funds:

- The money is no longer available for other purposes

- The government is legally required to pay when the bill comes due

- Breaking the commitment has legal consequences

This is why agencies track obligations so carefully. You can't obligate more than Congress appropriated (that's an Anti-Deficiency Act violation), and you can't obligate funds that haven't been apportioned by OMB.

Example

Congress appropriates $10 million for equipment purchases. The agency signs a contract to buy $3 million in computers.

- Before contract: $10M unobligated

- After contract: $7M unobligated, $3M obligated

- Cash in Treasury: Still $10M (nothing paid yet)

The obligation is recorded immediately. The outlay comes later, when the computers are delivered and the vendor is paid.

Outlays: The Payment

An outlay is an actual disbursement—money leaving the Treasury.

Outlays occur when the government actually pays vendor invoices, grant disbursements, employee paychecks, benefit payments, and loan disbursements.

The timing between obligation and outlay varies enormously by program type.

Fast vs. Slow Outlays

Back to the restaurant one more time. A glass of wine arrives immediately—you order, they pour, you drink, you pay. That's a fast outlay. But paella? That takes 30-45 minutes to cook. You've obligated the money when you order, but the kitchen is just getting started. Payment comes much later.

Fast outlays (obligation and outlay close together):

- Salaries: Obligated and paid within the same pay period

- Utility bills: Obligated when incurred, paid within weeks

- Direct benefit payments: Often same-month

Restaurant: Wine, coffee, dessert from the case

Slow outlays (significant lag between obligation and outlay):

- Construction contracts: May take years to complete and pay

- Multi-year grants: Disbursed over the grant period

- Major equipment: Paid upon delivery, which may be months/years away

Restaurant: Paella, soufflé, anything that takes time to prepare

Example (continued)

The agency obligated $3M for computers. Six months later, the computers are delivered and the vendor submits an invoice.

- At delivery: Agency pays the $3M invoice

- After payment: $3M is now "outlaid" (expended)

- Cash in Treasury: Now $7M (the $3M actually left)

The Outlay Rate

Different programs have different "outlay rates"—how quickly obligations turn into outlays.

| Program Type | Typical Outlay Rate (Year 1) |

|---|---|

| Salaries | ~100% |

| Operating expenses | 80-90% |

| Grants | 30-50% |

| Construction | 10-30% |

| Major procurement | 20-40% |

This matters for budget scoring and cash management. A $1 billion construction appropriation won't result in $1 billion leaving the Treasury this year—maybe only $100-300M will.

The policy implication: When Congress "cuts" a construction program, the immediate outlay savings are small. The big savings come years later when those future outlays don't happen.

Timing

While obligations must occur before the end of the period of availability, Congress has given agencies and grantees more time to outlay funds. Outlays can occur up to 5 years after the end of the period of availability.

The Lifecycle of a Federal Dollar

Here's the complete journey, using a single dollar as an example—with the restaurant parallel:

Stage 1: Appropriated

Congress passes an appropriations bill. The dollar is now available to the agency—but not yet released.

Restaurant: You have $250 in your wallet when you sit down.

Stage 2: Apportioned

OMB releases the dollar to the agency through an apportionment.

Restaurant: You open the menu and decide you can spend up to $75 on dinner tonight.

Stage 3: Obligated

The agency signs a contract that commits the dollar.

Restaurant: You order the entree. The kitchen starts cooking.

Stage 4: Expended (Outlaid)

The vendor delivers, submits an invoice, and Treasury pays.

Restaurant: You pay the check. Money leaves your wallet.

| Stage | Unobligated | Obligated (Unexpended) | Expended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriated | $1 | $0 | $0 |

| Apportioned | $1 | $0 | $0 |

| Obligated | $0 | $1 | $0 |

| Outlayed | $0 | $0 | $1 |

Every budget report is a snapshot of where dollars are in this lifecycle.

Real World Example

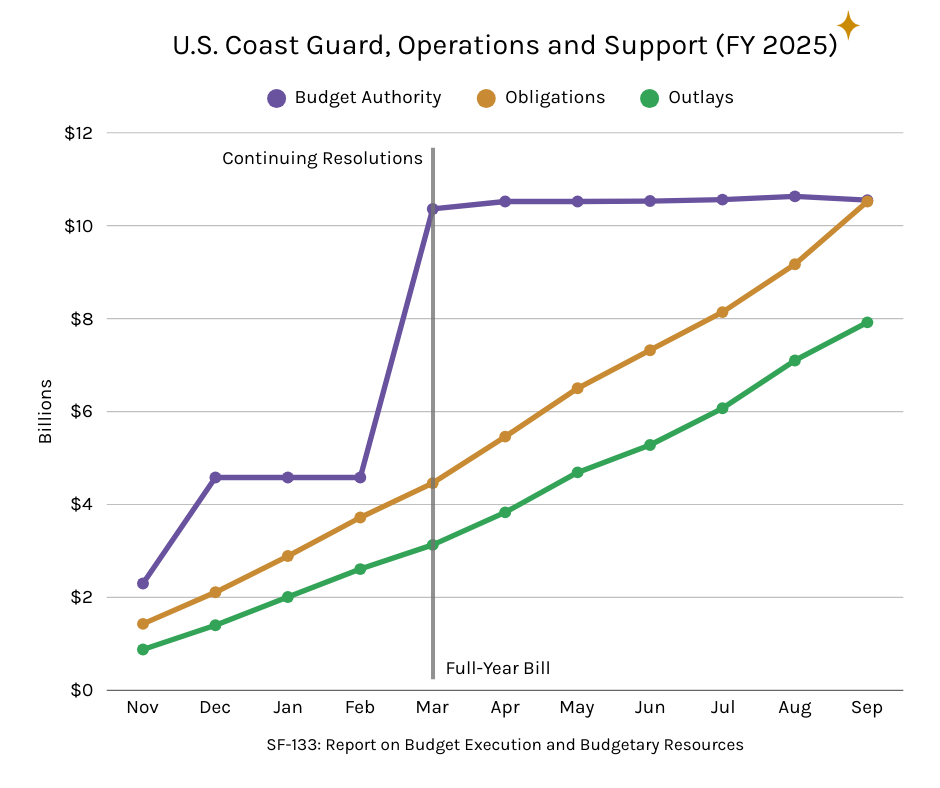

Here's what this looks like in practice. The chart below shows the U.S. Coast Guard's Operations and Support account for FY2025 (70-0610 /25)—one of the largest accounts in the Department of Homeland Security.

Three lines, three different stories.

- Budget authority (purple) arrives in chunks. Under continuing resolutions, it climbed in steps—each CR extended funding at prior-year rates. When the full-year bill passed in March, authority jumped to $10.5 billion and plateaued.

- Obligations (orange) climb steadily. The Coast Guard signs contracts, pays salaries, and commits funds throughout the year. By September, they'd obligated nearly all available authority—normal execution for an operating account.

- Outlays (green) lag behind. Even in a fast-outlay account like Operations and Support (mostly salaries and operating costs), actual payments trail obligations by $2-3 billion at any given point. That gap is money committed but not yet paid—your "obligated, unexpended" balance.

The key insight: at the end of August, these three numbers told three different stories:

- $10.5B in budget authority (what Congress provided)

- $10.5B in obligations (what the agency committed)

- $7.9B in outlays (what actually left the Treasury)

Same account, same moment, three different answers to "how much did they spend?"

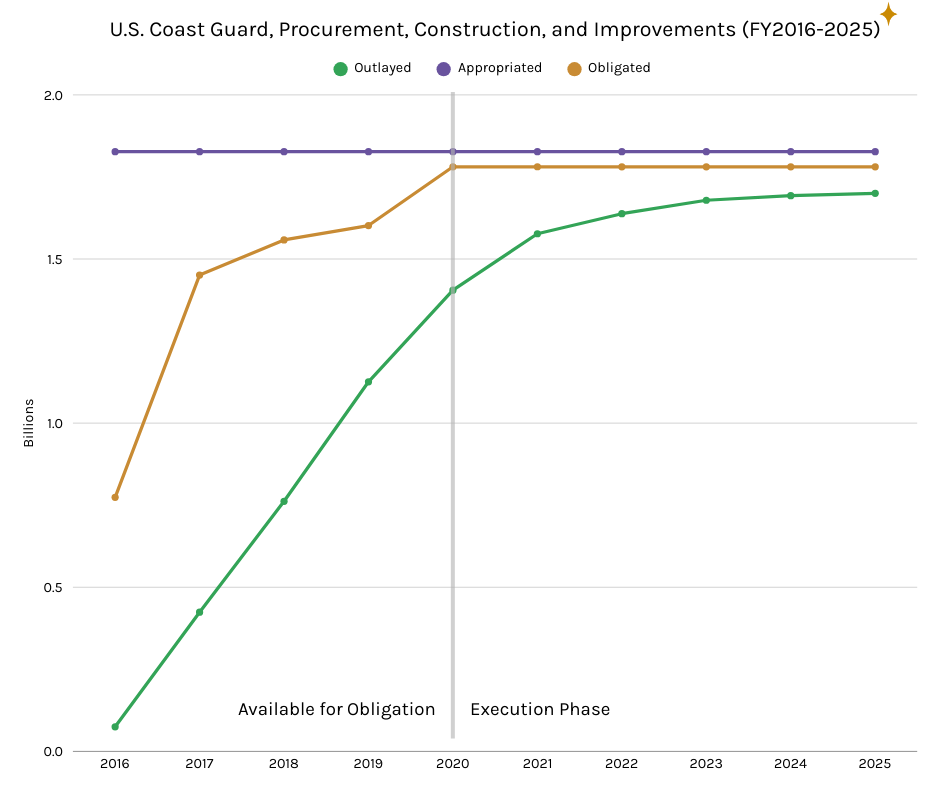

The slow burn: capital spending over a decade

The chart below tracks a single FY2016 appropriation for Coast Guard capital projects-70-0163 16/20—ships, aircraft, shore facilities. Unlike the operating account above, this is multi-year money with a 2016/2020 period of availability: Congress authorized the Coast Guard to sign contracts through September 30, 2020, but not after.

-

Appropriated (purple): $1.85 billion arrives in FY2016 and holds steady. Multi-year funds don't expire at year-end—they remain available until the obligation window closes.

-

Obligated (orange): The Coast Guard signs contracts steadily through 2020, committing nearly all funds by the deadline. After September 2020, the line flattens—no new obligations are legally permitted.

-

Outlays (green): This is the punchline. Ten years after appropriation, outlays still haven't caught up. Ships take years to build. Progress payments flow as milestones are met. By FY2025, only ~$1.7 billion of the original $1.85 billion has actually left the Treasury.

Why This Matters for Tracking

When you see a headline like "Agency spent $500 million on Program X," ask: appropriated, obligated, or outlaid?

Appropriations tell you:

- What Congress authorized

- The legal ceiling for the program

- Policy intent (but not execution)

Obligations tell you:

- What the agency has committed to

- Current-year decisions and priorities

- Whether they're using their appropriation

Outlays tell you:

- What actually went out the door

- Cash flow impact on the deficit

- Program execution (work actually happening)

Common Confusions

"We cut spending by $100M"

Did obligations go down, or just outlays? Cutting a construction project might reduce obligations immediately but barely change outlays this year.

"The program is underspending"

Low obligations = possible problem (agency not using funds). Low outlays with high obligations = normal for slow-outlay programs.

"Year-end spending spree"

Agencies obligate funds before fiscal year end. Delays in appropriations on the front end often mean agencies need to rush to commit funds before their ability to use them expires. This doesn't mean cash went out—just commitments were made.

Understanding this distinction is fundamental. Everything in the apportionment and SF-133 builds on it.

The Bottom Line

Appropriations, obligations, and outlays are the three heartbeats of federal spending:

- Appropriations show authority—what Congress authorized

- Obligations show commitment—what agencies promised to pay

- Outlays show execution—what actually left the Treasury

Master these distinctions, and budget documents start making sense. Confuse them, and you'll misread every report you encounter.

What's Next

Now that you understand appropriations, obligations, and outlays, you're ready to read the documents that track them. Next up: How to Read an Apportionment—the document that controls when and how agencies can obligate their appropriated funds.

BlazingStar Analytics is building real-time budget execution tracking that connects appropriations, apportionments, and SF-133 reports. Get early access to our platform, launching Spring 2026.