What is an apportionment?

Congress appropriated $198 million. But the agency can only spend $55 million this quarter. What happened to the rest?

1. What is an apportionment?

2. How to Read an Apportionment, Part I: Structure and Time-Based Controls

3. How to Read an Apportionment, Part II: Footnotes and Legal Weight

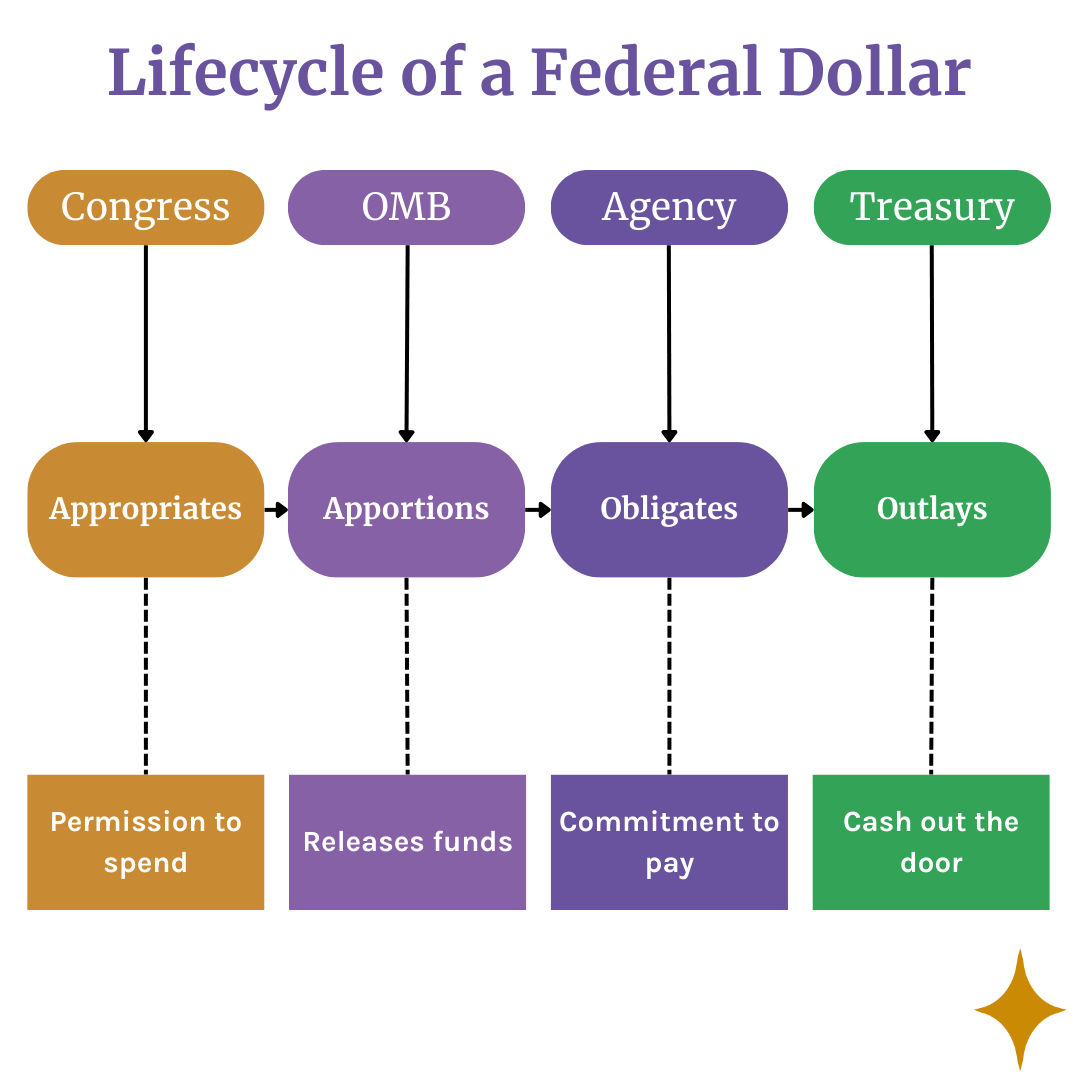

If you've been following this blog, you know the three stages of federal spending: appropriation, obligation, outlay. Congress provides the authority. Agencies commit the funds. Treasury pays the bills.

But there's another stage that most people miss—one that sits between Congress and the agencies, quietly measuring out and controlling the pace and flow of federal dollars.

It's called apportionment. And it might be the most important budget document you've never heard of.

The 60-Second Version

| Term | What It Means | Restaurant Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Apportionment | OMB's formal release of appropriated funds to agencies | Deciding you'll only spend $100 of the $250 in your wallet tonight |

Key insight: Congress appropriates. OMB apportions. These are not the same thing.

An appropriation gives an agency permission to spend. An apportionment tells them how much they can actually obligate, and when.

Until OMB apportions funds, agencies cannot legally commit a single dollar—even if Congress appropriated billions.

Download a quick visual explainer on apportionments.

Why Apportionment Exists

To understand apportionment, you need to understand the problem it was designed to solve.

In the early 20th century, federal agencies had a habit of spending their entire annual appropriation in the first few months of the fiscal year—then coming back to Congress mid-year, hat in hand, asking for more money. Congress, faced with the choice of letting programs shut down or providing emergency funds, usually caved.

This was not a sustainable system.

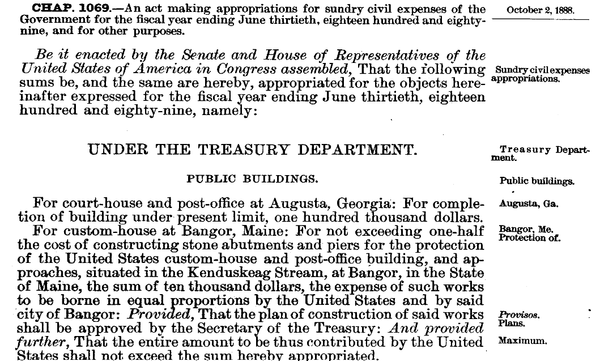

The Anti-Deficiency Act, originally passed in 1870 and significantly strengthened in the 1920s, and The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 created the apportionment system we have today. (For the full legal history, see our post on The Constitutional and Legal Framework.)

The law requires the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to divide appropriations into amounts available for specific time periods—usually quarters. Agencies cannot obligate funds faster than OMB releases them.

Translation: OMB acts as a regulator on the spending engine. Congress fills the tank. OMB controls the fuel line.

Where Apportionment Fits

Remember the lifecycle of a federal dollar from our previous post? No? Here's the chart again:

Most budget coverage skips straight from appropriation to obligation. That's a mistake. The apportionment step is where executive branch priorities actually get implemented—where abstract congressional intent becomes concrete spending authority.

The Restaurant Analogy (Continued)

We've been using a restaurant metaphor throughout this series. Here's how apportionment fits:

-

Appropriation: You have $250 in your wallet when you sit down. That's your budget authority—money available to spend.

-

Apportionment: You open the menu, check the prices, and decide you'll only spend $100 on dinner tonight. You're keeping $150 in reserve.

-

Obligation: You order the steak ($45). You've committed to pay.

-

Outlay: You pay the check. Money leaves your wallet.

The apportionment decision—"I'll spend $100 tonight"—happens before you order anything. It's a constraint you impose on yourself (or in the federal case, that OMB imposes on agencies).

And just like you might have good reasons to hold back some of your cash—saving for tomorrow, unexpected expenses, that concert next week—OMB has legitimate reasons to apportion less than the full appropriation.

But sometimes the reasons aren't legitimate. And that's when apportionments become politically important.

What an Apportionment Controls

OMB apportionments control three things:

1. Amount

How much of the appropriation is released. OMB can apportion the full amount or hold some back.

2. Timing

When funds become available. Most apportionments divide annual appropriations into quarterly amounts. An agency might have $100 million for the year, but only $25 million available in Quarter 1 (Q1).

3. Purpose

Which programs or activities can use the funds. OMB can specify that certain amounts are for specific purposes—$40 million for grants, $10 million for administration.

These controls are implemented through a category system:

| Category | Controls By | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Category A | Time period | $25M per quarter |

| Category B | Program/project | $40M for grants, $10M for admin |

| Category C | Future fiscal years | $100M available in FY2026 |

4. Conditions

An apportionment can also impose conditions on how an agency can use funds.

For example: requiring a spend plan before all funds are available, requiring regular briefings, or, more recently, requiring that certain funding comply with executive orders. OMB usually adds these restrictions through an apportionment footnote.

We'll cover this system in detail in our next post, "How to Read an Apportionment." For now, just know that OMB has precise tools for controlling the pace and direction of federal spending.

Agency Requests, OMB Approves

After Congress passes, and the president signs, an appropriations act, the apportionment process begins when an agency submits an apportionment request to OMB. OMB receives the request; the relevant branch reviews it, asks questions, and sometimes proposes modifications to the agency request.

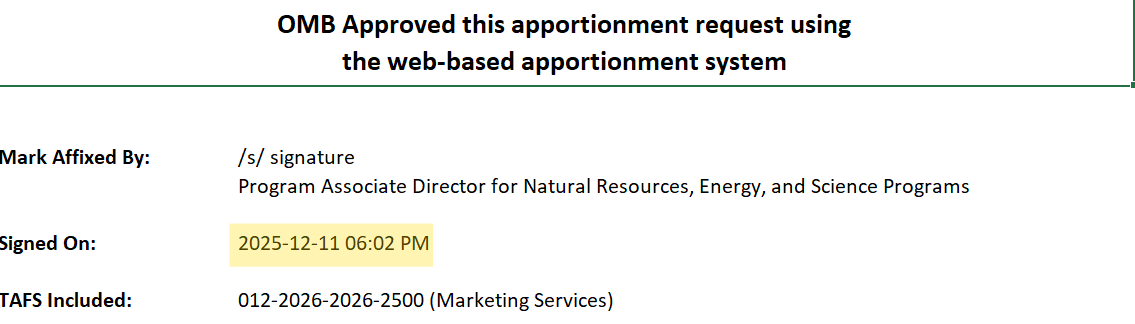

There is internal review within OMB, moving the request from the budget analyst, to the branch chief, on to the Deputy Associate Director, and finally on to the Program Associate Director. Once the Program Associate Director approves the apportionment, it has full force and effect.

Apportionments During a Continuing Resolution

If you're looking for an apportionment during a continuing resolution, you may not find one.

When a CR passes, OMB doesn't issue hundreds of individual apportionments for the CR period. Instead, it issues a single bulletin that automatically apportions funds for all covered programs. Here's the bulletin that apportioned funds for the FY 2026 CR through January 30, 2026.

The math is straightforward: OMB calculates a pro-rata amount based on how long the CR lasts (days in CR ÷ days in year). Section 4 of that bulletin walks through the calculation. For the detailed framework, see Section 123 of Circular A-11.

Exceptions to Automatic Apportionments

Spend Faster. Some accounts can spend above the pro-rata rate. These "spend faster" anomalies appear as account-specific provisions in the CR, usually with language like "may be apportioned up to the rate for operations necessary..."

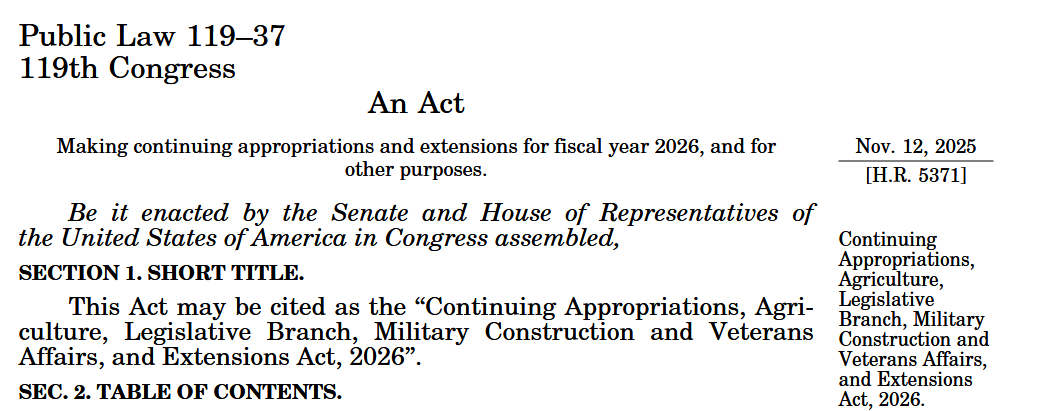

Here's an example from the current CR:

Sec. 147. Amounts made available by section 101 to the Department of Homeland Security under the heading "Federal Emergency Management Agency—Disaster Relief Fund" may be apportioned up to the rate for operations necessary to carry out response and recovery activities under the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5121 et seq.).

FEMA's Disaster Relief Fund can spend faster than the standard CR rate—because disasters don't wait for appropriations bills. To use this authority, the agency requests an account-specific apportionment, and it shows up in the public system.

Zero Apportionments. At the other end: accounts that received $0 in either the House or Senate bills automatically get $0 under the CR bulletin. CRs typically include language like this:

Sec. 110. This Act shall be implemented so that only the most limited funding action of that permitted in the Act shall be taken in order to provide for continuation of projects and activities.

OMB implements Section 110 by automatically apportioning zero. If an agency needs funding for specific activities during the CR period, it provides written justification—and OMB issues an account-specific apportionment for a specific amount.

How to Read a Continuing Resolution

The Gap That Matters

Here's why apportionment matters for anyone tracking federal spending:

The amount Congress appropriates and the amount OMB apportions are often different.

Sometimes this gap is routine:

- Multi-year funds: A 5-year appropriation of $500M might be apportioned at $100M per year

- Seasonal programs: A wildfire suppression account might get most of its funding apportioned for the summer

- Timing: Early in the fiscal year, not all funds are immediately needed

Sometimes this gap is concerning:

- Policy disagreement: The administration doesn't want to spend money that Congress directed

- Impoundment: Funds withheld without following legal procedures

- Slow-walking: Delays that effectively kill programs without formally canceling them

The same goes for account-specific apportionments during a CR. If the amount differs significantly from what the account would receive under automatic apportionment, there has to be statutory authority—or a good reason worth asking about.

The apportionment is where you see executive branch priorities in action—not press releases, not budget requests, but actual decisions about which dollars flow and which ones don't.

A Real Example

Let's look at an actual apportionment to see how this works in practice.

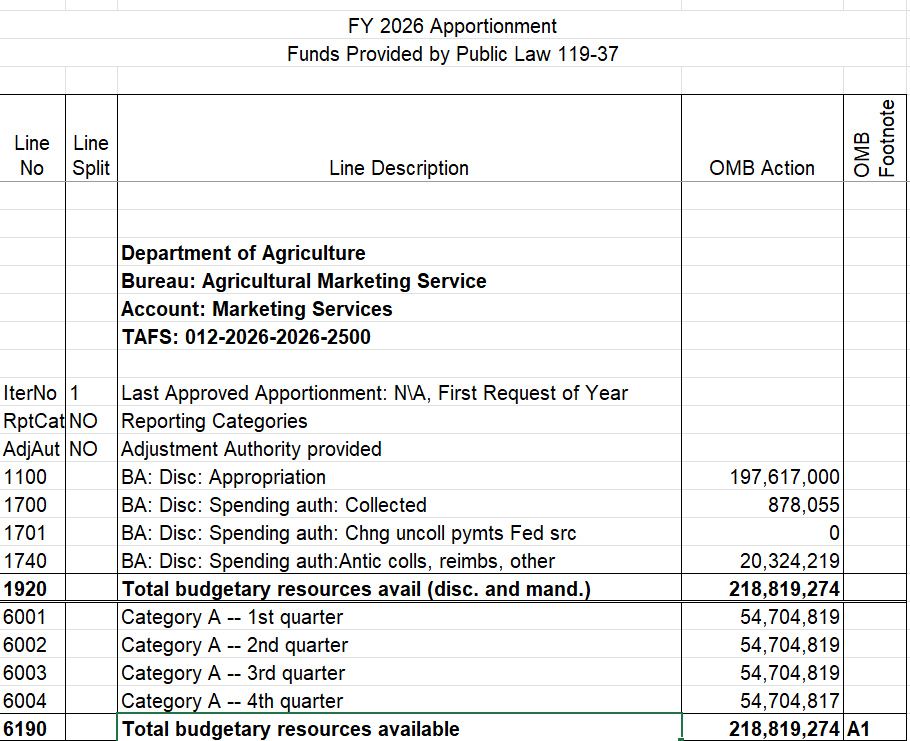

Here's the most recent apportionment for USDA's "Marketing Services" account in the Agricultural Marketing Service. This apportionment was approved on December 11, 2025 and makes funds available from the recent omnibus.

You can see this apportionment for yourself at: OMB or OpenOMB.org

At the beginning of the apportionment, you can see:

- The fiscal year (2026)

- Legal source (P.L. 119-37)

- Agency (Department of Agriculture)

- Bureau (Agricultural Marketing Service)

- Account (Marketing Services)

- TAFS (012-2026-2026-2500)

- Iteration (1)

The rest is the more interesting part, and is divided into two halves that balance:

- The top half (1XXX lines) describes the budgetary resources available

- The bottom half (6XXX lines) describes the application of those budgetary resources

See how lines 1920 and 6190, both $218,819,274, are equal? That's because the two halves are talking about the same money.

Lines 1100-1740 describe all the funds available to this account in this fiscal year: an appropriation of $197.6 million, $878,055 in fees collected so far, and an estimated $20,324,219 more in fees during the year. All of these sources total to $218,819,274.

Lines 6001-6004 apportion the total amounts into fiscal quarters. In this case, the funds are spread evenly across all four quarters. These sum to $218,819,274; note that the funding in Q4 was adjusted down by $2 to ensure the total balances exactly.

You might be asking yourself, "Where is the date that it was approved?" In the Excel version it's on a separate tab, like this:

It also shows who approved the apportionment, in this case, the Program Associate Director for Natural Resources, Energy, and Science Programs.

We will go into how to unlock all of the meaning and complexities in an apportionment in our next two posts, but knowing that there are two halves (total resources and application of resources) and that they balance is key.

Where to Find Apportionments

Until recently, apportionments were largely invisible to the public—internal documents shared between OMB and agencies. That's changed.

Official Source: OMB MAX Portal

The Office of Management and Budget publishes current apportionments at:

This is the authoritative source. Documents here are the actual apportionments in effect. Data is available in both Excel and JSON.

OpenOMB.org

For easier searching and comparisons between versions, try:

OpenOMB provides a searchable archive of apportionments with historical data, making it easier to track changes over time and compare across agencies.

What to Look For

When you pull an apportionment, note:

- Version number: Apportionments change frequently. "Version 7" means six previous versions this fiscal year.

- Effective date: When this version became active

- Account symbol (TAFS): The unique identifier for this appropriation account (see our post on The TAFS)

Why Should You Care?

If you work in federal policy, government contracting, grants, or journalism, apportionments answer questions that appropriations can't:

"Congress appropriated $500 million for this program. How much is actually available?"

Check the apportionment. The answer might be $500 million—or it might be $200 million.

"Why isn't this program spending its money?"

It might be an agency execution problem. Or OMB might not have released the funds. The apportionment tells you which.

"Is the administration slow-walking this program?"

Compare the apportionment to the appropriation. A large unapportioned balance late in the fiscal year is a red flag.

"When will these funds actually be available?"

The apportionment shows quarterly release schedules. Q4 funds aren't available in Q1.

The Bottom Line

Apportionment is where congressional intent meets executive action.

Congress can appropriate all the money it wants. If OMB doesn't apportion those funds, they don't flow. Understanding this dynamic is essential for anyone trying to track what the federal government is actually doing with taxpayer dollars.

Key takeaways:

- Appropriation = permission to spend (from Congress)

- Apportionment = release of funds (from OMB)

- These are not the same thing

- The gap between them is where policy happens

What's Next

Now that you understand what an apportionment is and why it matters, you're ready to learn how to read one. In our next post, we'll walk through the structure of an apportionment document—the sections, the line numbers, and how to find the information you need.

BlazingStar Analytics is building real-time budget execution tracking that connects appropriations, apportionments, and SF-133 reports. Get early access to our platform, launching Spring 2026.